Visuelle Kommunikation

Master

María Marín de Buen

Alternative Temporalities –

Exploring the visualization of time

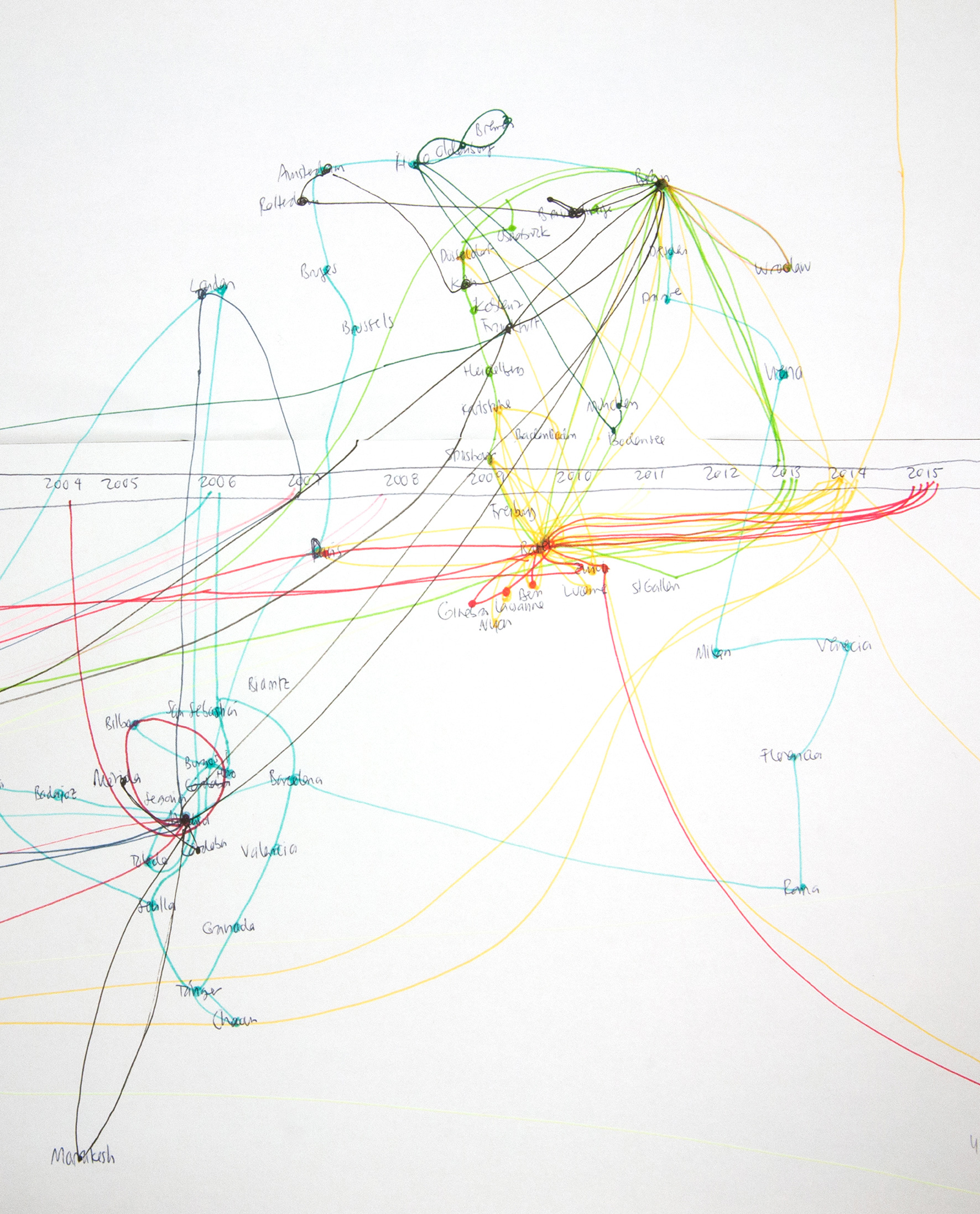

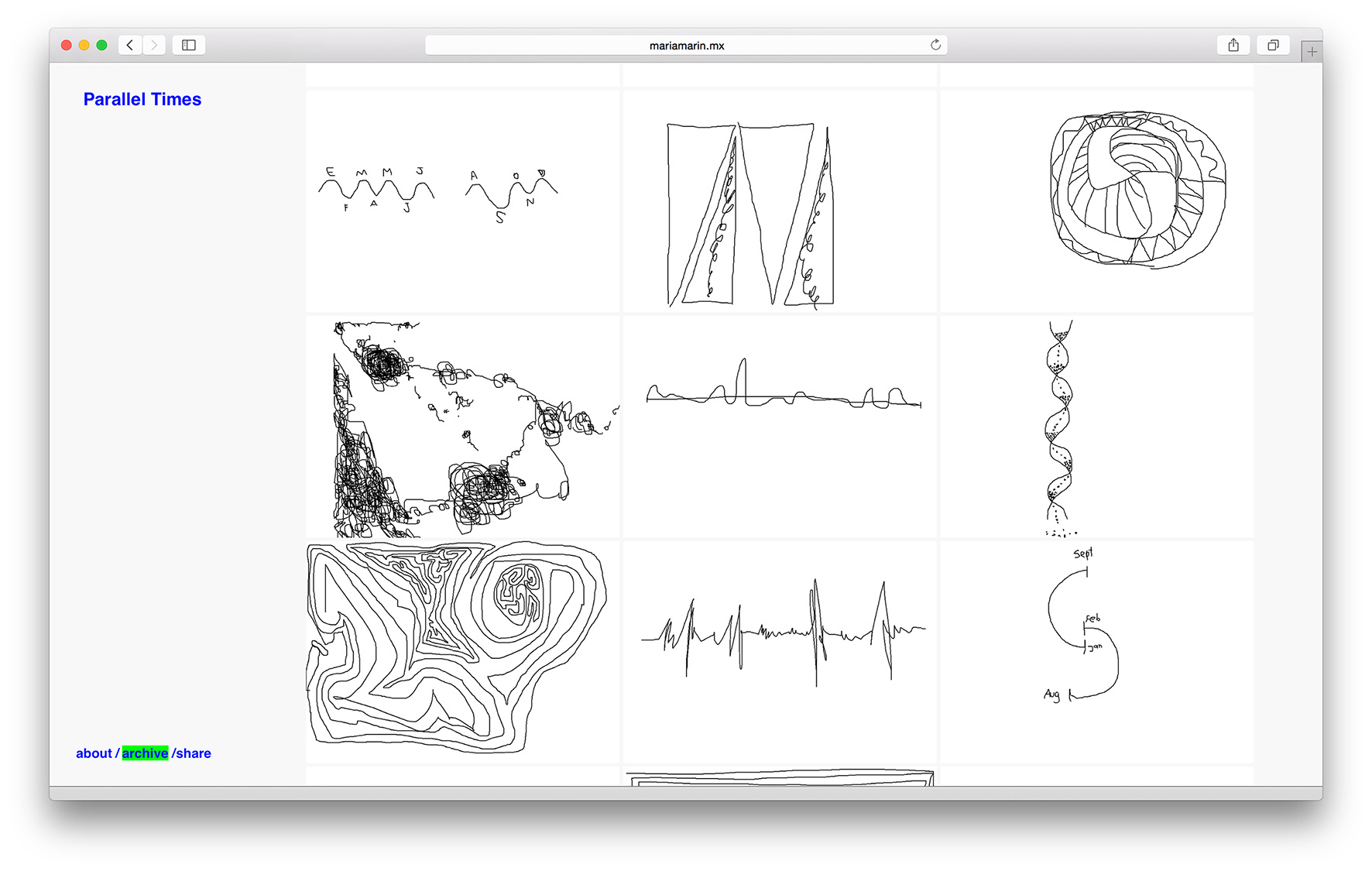

We all know what time is, but it gets complicated when we try to put it in words or images. Is time something natural and preexisting, or rather something fabricated and moldable? My thesis project questions the influence of conventional time-keeping objects on the individual perception of time.

Time is a complex subject since it relates to every aspect of our existence. What is time? Who can explain it? As St. Augustine said: “If no one asks me, I know what it is. If I wish to explain it to him who asks me, I do not know.”1 Time is something futile, ephemeral, non physical, but nevertheless something sizeable and countable. It can be related to motion, from the moving planets and stars, to the continuous ticking of a clock, or the different stages of human life. Time in words of George Woodcock is a category so elusive that no philosophy has yet determined its nature.2

Why does it appear accelerated as we get older? Why does it fly for those having fun, but feels eternal for the bored? Why does time seem slower when facing a life-threatening experience? Rather than giving answers to the many questions that rise while dealing with the topic of time, my thesis provides diverse possibilities to look at time in a differentiated way.

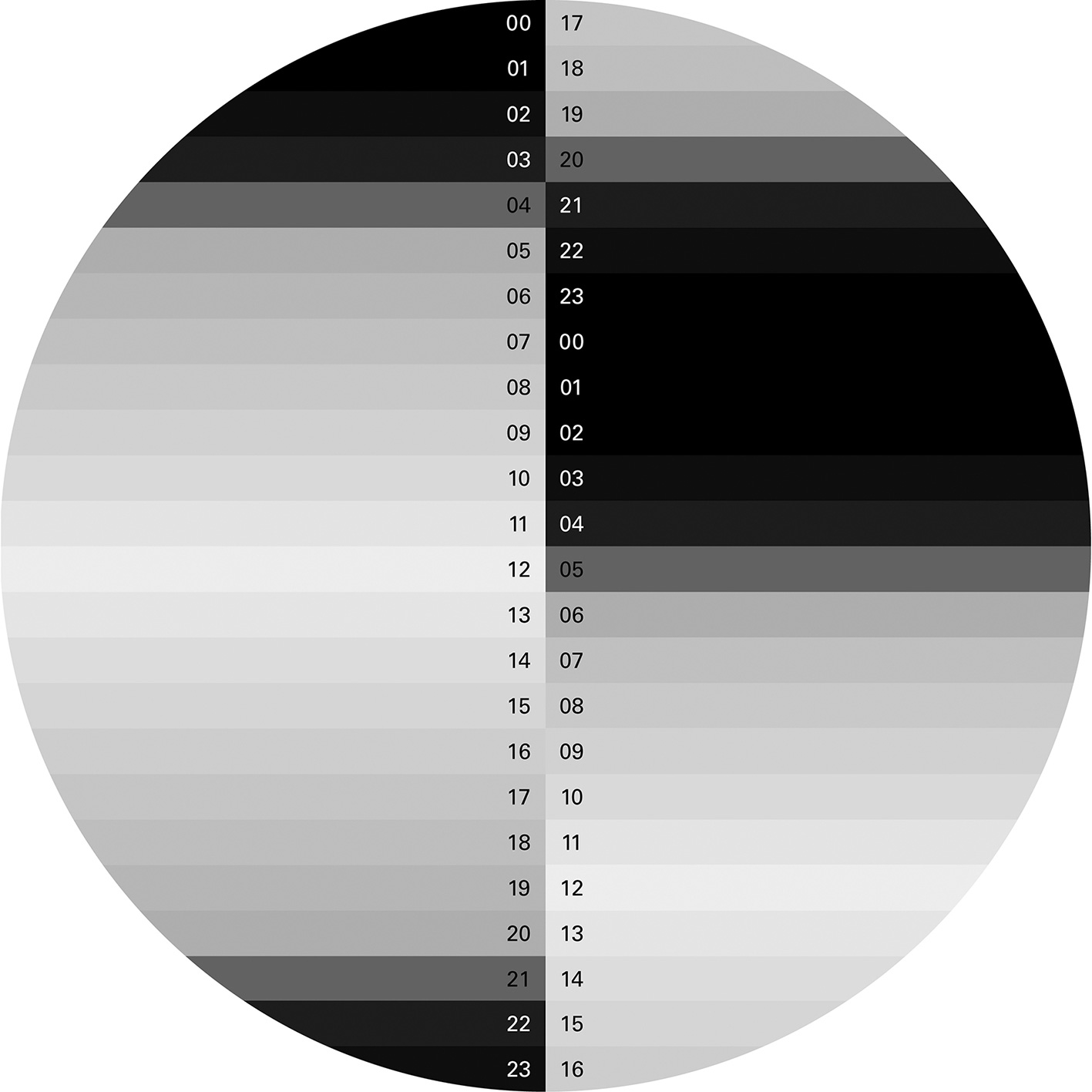

The interaction, communication and relationships between humans would be impossible without time structures. As E.P. Thompson showed, the universal observance of clock time is a consequence of the industrial revolution. He argued that the creation of the modern state would not have been possible without the imposition of what he termed “time discipline.”3 This set of economical conventions, regulations and expectations concerning time measurement, can only exist with the presence of standardized units of duration. Such units, like seconds, minutes, hours, days, weeks, months, years, etc., all characterize time but they don’t stand for a coherent cultural system, instead, they represent the accumulation of a variety of solutions to the diverse temporal problems. These units are useful in measuring durations of what happens in our lives, but the relationship to our world is hardly straightforward. What is an hour? It is not defined by a natural cycle4; there are no millennial cycles in nature and the Gregorian calendar and the atomic clocks we use to keep track of time have known inaccuracies.5 Even if the logic of our time systems is questionable, we are still passionately accustomed to them.

The correspondence between our individual handling of temporality and the standardized models is as complex, if not more. Are all humans “on” the same time? The patient in the dentist’s chair and the audience listening to a Beethoven symphony experience the same atomically tagged duration in quite different ways.6 My thesis project generates an awareness of how our time perception is determined by technological, cultural, social and psychological aspects. It will raise consciousness of

the conventions, rules and habits we are used to.

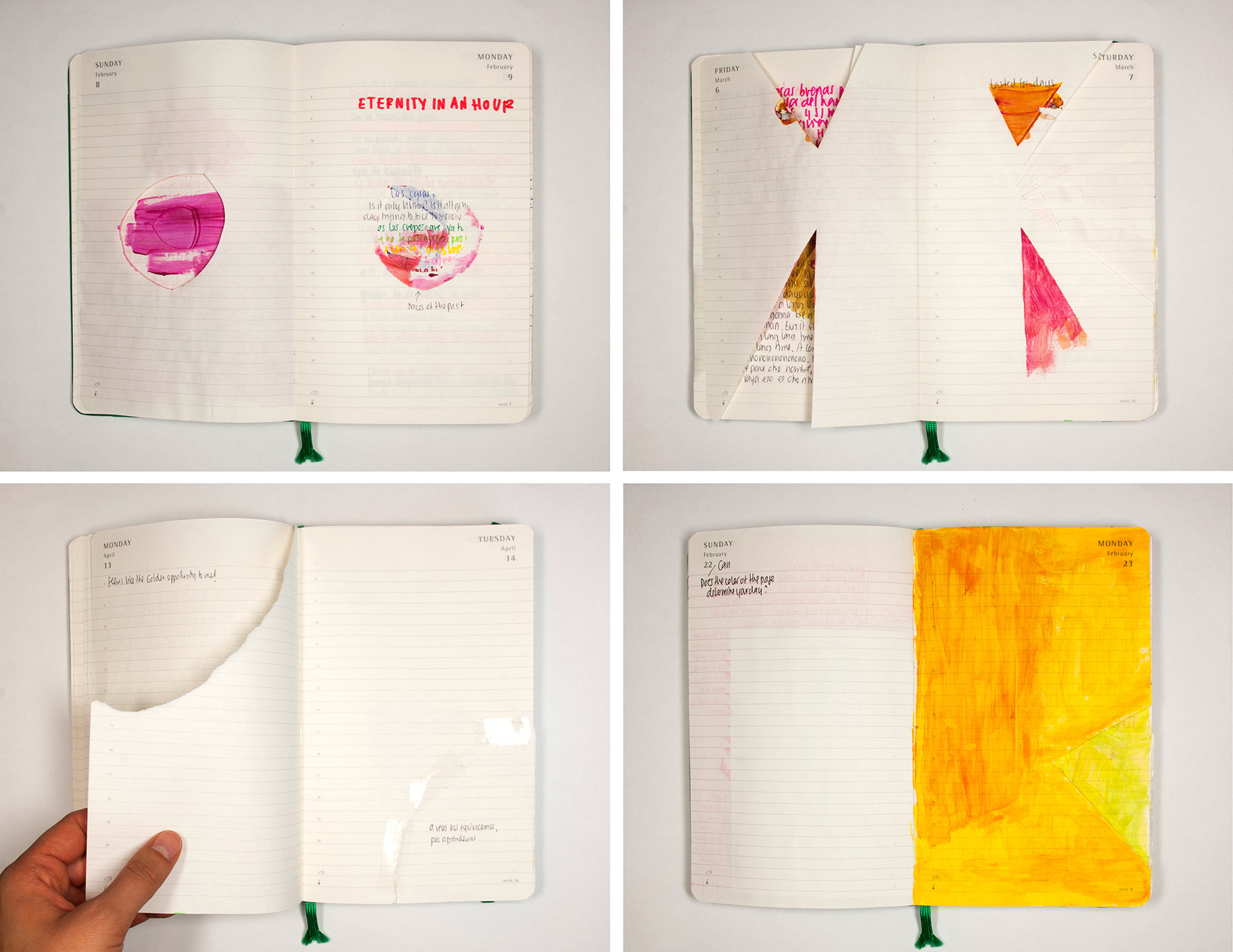

Despite the fact that in our minds we all visualize time in a very unique manner, there are existing metaphors that commonly define how time should look like such as calendars and agendas. These tools convert time’s immateriality in measurable entities providing a sensation of substantiality and orientation. However, it is of great importance to observe how agendas and calendars also give conditions and constrains to our perception of time. It is challenging to think of time without considering what the time-keeping tools command.

The Gregorian calendar conventionally represents time across cultures, and its structure is deeply rooted in our minds. We barely question its origin, its impact and the influence it has on our daily routines. The way it is commonly visualized (whether it is on a wall calendar, an agenda or a digital calendar) serves a particular purpose and favors one representation of time, diverting our consciousness of the parallel, intersecting times we experience every moment. As Elias wrote, “knowledge of

calendar time … is taken for granted to the point where it escapes reflection” and such lack of reflection easily leads to the unquestioned acceptance of a calendar’s logic.7

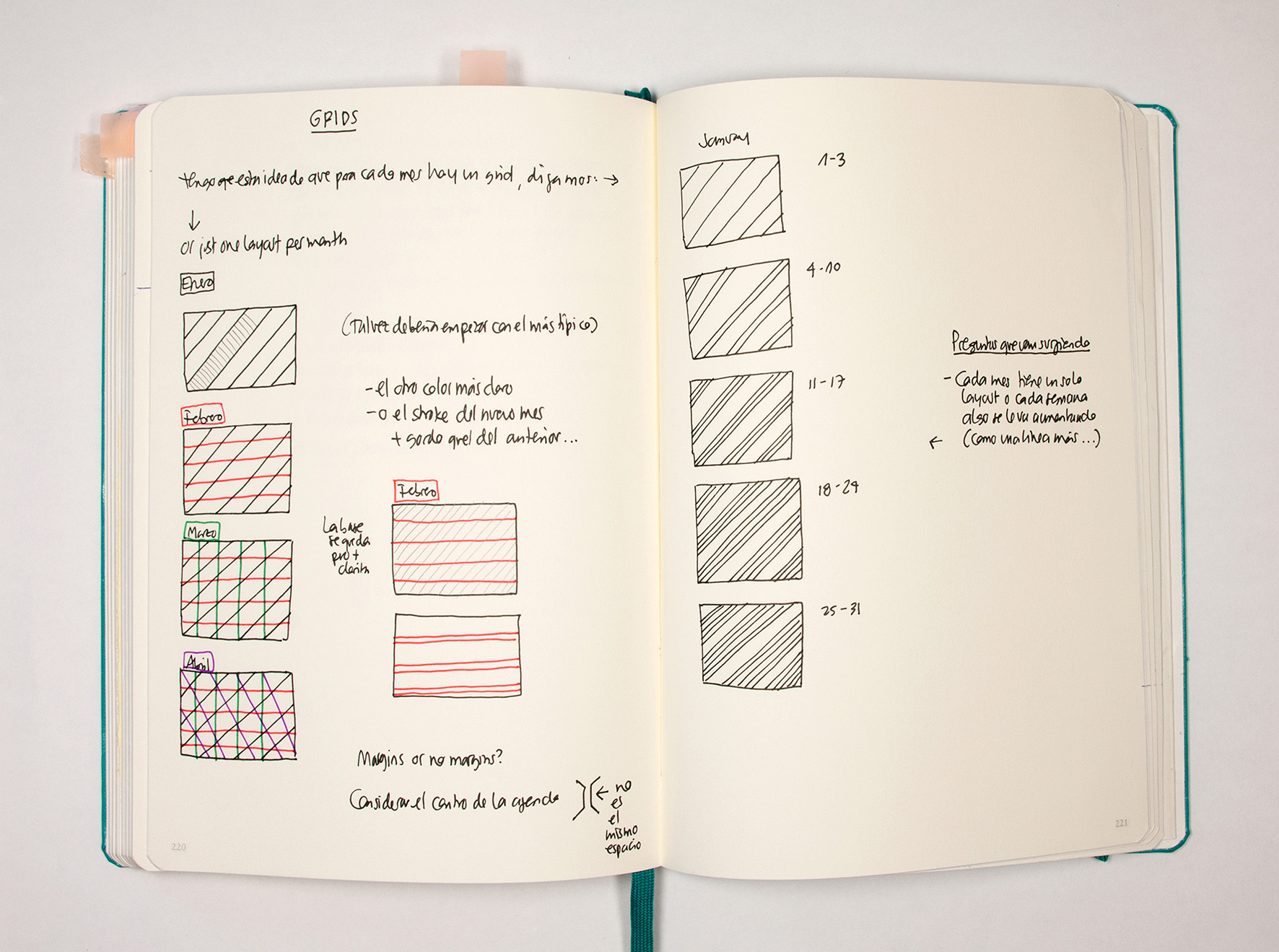

By deconstructing the Gregorian calendar and considering other temporalities, this project offers alternative time-keeping tools. The outcome is a series of agendas in which unconventional structures are explored.

María Marín de Buen

Institut Visuelle Kommunikation, FHNW HGK, Freilager-Platz 1, CH-4023 Basel

+41 61 228 41 11, info.vis_com.hgk@fhnw.ch, www.fhnw.ch/hgk/ivk